When I started writing On Wilder Seas eight years ago, I wanted to counter the hero narrative surrounding Francis Drake, which persists despite his background in the slave trade.

So I’m delighted that the Black Lives Matter movement brought the issue to the fore. In early June, calls were made for Drake’s statues in Plymouth and Tavistock to be removed, after protesters toppled Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol.

Too often in the UK, Drake is presented as an unqualified hero: the brave circumnavigator who saved England from the Spanish Armada; his role in the slave trade glossed over or unmentioned. But how culpable was he? As I found out while researching my book, the answer is not straightforward.

Details of Drake’s early life are sketchy, but Drake’s first slaving voyage was most likely with John Lovell’s fleet in 1566-67. According to Emory University’s Transatlantic Slave Trade Database, the Englishmen enslaved about 300 people in Sierra Leone, transported and sold them in Venezuela and Colombia.

Drake sailed again in November 1567, this time with his kinsman John Hawkins, who had led England’s first slaving mission in 1562. Drake joined Hawkins’ fleet of seven ships, two of which were supplied by the Queen.

The details of this voyage are painful to read. At Sierra Leone, the Englishmen allied with two local kings to besiege a town near modern-day Freetown.

As Hawkins wrote: “I went myself and with the help of the kyng of our side assaulted the towne bothe by land and sea and very hardly with fyre (their houses beinge covered with drie palme leves) obtayned the towne and put the inhabitants to flight where we toke 250 persones, men women and children.”1

In fleeing the attack, thousands of people were driven into a swamp and drowned.

In addition to another 250 Africans taken elsewhere in Sierra Leone, the fleet sailed for the West Indies on February 3, 1568, with 500 captives. Most had been sold in the Americas when Hawkins turned for home – but caught in a hurricane, he was forced to harbour at San Juan de Ulua in Mexico, where the fleet was attacked by the Spaniards.

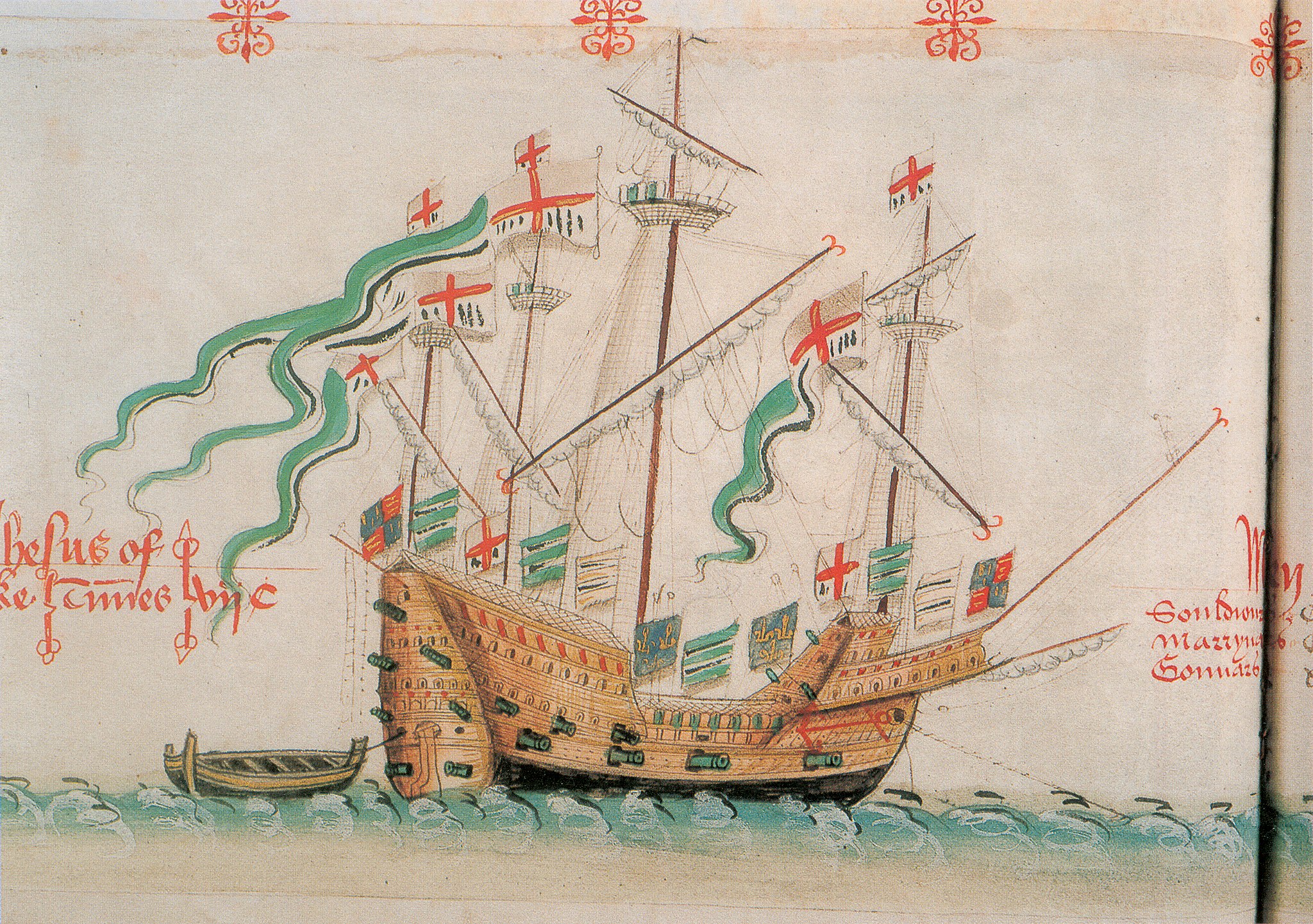

Amid fierce fighting, the English lost four ships: the Angel was sunk; the Grace of God set on fire; the Jesus of Lubeck badly damaged and the Swallow taken. At the height of the battle, Drake, in command of the Judith, escaped – or as Hawkins later put it, “forsook us in our great misery.”2

Hawkins offloaded as much of his treasure as he could from the Jesus to the Minion and also escaped. But forty-five Africans, still chained in the holds of the four lost ships, were left to their fates.

In March 1569, Hawkins listed the value of his losses at San Juan de Ulua for the Admiralty Court. Alongside gold and silver, bales of taffeta, cotton and woollen cloths, he added “fifty-seven Negroes in the Jesus and the three other ships aforesaid, each worth in the West Indies 400 pesos of Gold at 8s. the Peso.”3 This amounted to £9,120 – more than the combined value of all four ships lost in the battle. The 700-ton Jesus of Lubeck, loaned by the Queen, was valued at £5000.

The voyage was so disastrous that it put an end to English slave trading for the next 70 years.

It also sent Drake in a different direction. Fuelled by desire for revenge against the Spaniards, Drake turned to the West Indies. On his third voyage there in 1572, he met Diego, a Cimarron – an African fleeing slavery – in Panama. A record of the voyage describes how Diego rowed to Drake’s ships and asked if they belonged to the now infamous English captain. According to the record of the voyage: “Upon answere received, [he] continued entreating to be taken aboard though he had first 3 or 4 shot made at him.”4

Diego was pivotal to the success of this voyage. He introduced Drake to Pedro, the ‘chief Cimarron’, who led Drake to attack a Spanish mule-train loaded with treasure. When Drake returned to England in 1573, his name and a small fortune made, Diego went with him. Four years later, when Drake set out on his circumnavigation voyage in 1577, Diego sailed too – as a free man.

Drake’s attitude to slavery appears to have changed since his earlier voyages. Off the coast of Mauritania, Drake was offered a woman: “a Moore (with her little babe hanging upon her dry dugge, having scarce life in herselfe, much lesse milke to nourish her child), to be sould as a horse, or a cow and calfe by her side, in which sort of merchandise our generall would not deale.”5

A witness aboard the Golden Hind reported that he still spoke of the Cimarrons of Panama with affection: “Captain Francis [said] that he loved them, speaking well of them and enquiring every day whether they were now peaceful.”6

Indeed, during the circumnavigation, a number of Africans are reported joining and leaving the Golden Hind. Those that stayed, appear to have been there voluntarily. One man, who had been taken aboard at Arica in Chile, had asked to return to his elderly master. Setting him ashore, Drake said: “I do not wish to take anyone with me against his will.”7

At Guatulco in Mexico, Drake attacked the town and found three Africans on trial in the courthouse. All were taken aboard the Golden Hind, but one, who said he was “willing to stay in the contry on lande” was released ashore “to save himself”.8

By the time the Golden Hind left Guatulco, three African men remained on board: Diego; one man taken from a ship near Paita; and one man from Guatulco.9 Given that Drake set ashore at least two men who asked him to, it seems likely all had chosen to stay.

They would have had good reason to do so. Numerous reports of enslaved people in the New World suggest they had heard the rumour that slavery was not legal on English soil, which was true in theory, if not in practice.

All this has a bearing on the fundamental premise of my novel.

On April 4, 1579, in the middle of his circumnavigation voyage, Drake attacked another Spanish ship near Guatemala. This time he did something very unusual: he took a woman.

Maria, an enslaved African, was sailing with the aristocrat Don Francisco de Zarate.

Historians have long assumed she was taken aboard the Golden Hind to provide sexual services. As Drake’s biographer Harry Kelsey put it: “The trip across the Pacific was going to take seventy or eighty days, and there was no sense in getting lonely.”10

But after learning about the African men who sailed with Drake voluntarily, I chose to afford Maria the same possibility of agency. Might she, too, have heard the rumours about freedom in England? Compared to the certainty of enslavement amongst the Spaniards, she had little to lose.

This article first appeared in Historia Magazine, in June 2020

Footnotes:

1 John Hawkins, A True Declaration of the Troublesome Voyage of M. John Hawkins to the parts of Guinea and the West Indies in the years of our Lord 1567 & 1568

2 John Hawkins, The Troublesome Voyage

3 This includes the ‘lost sale value’ of 12 Africans who survived the battle; seven returned to England with Hawkins on the Minion and five died on the journey.

4 British Library, Sloane MS301

5 The World Encompassed by Sir Francis Drake, 1628

6 Testimony of Nicolas Jorje, in Zelia Nuttall, New Light on Drake

7 Testimony of Juan Anton, in Zelia Nuttall, New Light on Drake

8 British Library MS280

9 Deposition of John Drake, March 24, 1584

10 Harry Kelsey, Sir Francis Drake: The Queen’s Pirate

Image: The Jesus of Lubeck from The Anthony Roll of Henry VIII’s Navy